Outside ensuring loose coupling, another major reason for using a dependency injection (DI) container, or IOC container, is controlling the instantiation and life cycle of dependencies. The case of life cycle is particulary important for types that represent read-only static data (e.g. a background image, some configuration, etc.) Two instances of such a type are identical. Their instances are generally created only once—as singletons—to avoid memory wastage.

All of these seems very obvious. However, trying a new concept in small prototypes and visualizing the impact gives better grip and confidence on it. Here, I share a minimal example that demonstrates how life cycle of types representing static data affects memory usage, how creating them as singleton improves memory usage, and how a DI container helps controlling their life cycle. The example is similar to something that I tried during my first days with dependency injection and I still like to show it to beginners.

Setup

My setup has a simple console application with Microsoft Unity as the DI container. The application consists only of the following types:

- HeavyWeightDependency. A type that holds read-only static data and has a high memory footprint; it holds a ~11 MB byte array (intentionally large so that impact is easier to observe) and it has no dependencies. We will inject instance of this type into a client type and observe the resultant impact on the application.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

internal class HeavyWeightDependency

{

private readonly byte[] _image;

public HeavyWeightDependency()

{

_image = File.ReadAllBytes("large-image.jpg");

}

}

- Client. This type is dependent on an instance of

HeavyWeightDependencythat is injected through its constructor. It also exposes the injected dependency as a read-only public property.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

internal class Client

{

public HeavyWeightDependency HeavyDependency { get; }

public Client(HeavyWeightDependency heavyDependency)

{

HeavyDependency = heavyDependency;

}

}

- Application Entry Point. The usual C# console application entry point: the

Programclass withMainmethod. The application essentially does nothing other than resolving aClientinstance iteratively from an Unity container every one second. It can also control the lifecycle ofHeavyWeightDependency(first commented block in theMainmethod) and append the dependency from the resolvedClientinstance into a static list (second commented block in theMainmethod.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

public class Program

{

private static IUnityContainer Container { get; } = new UnityContainer();

private static IList<HeavyWeightDependency> _dependencies =

new List<HeavyWeightDependency>();

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

//Container.RegisterType<HeavyWeightDependency>(

// new ContainerControlledLifetimeManager());

for (var i = 0; i < 40; i++)

{

Console.WriteLine($"iteration: {i}");

var client = Container.Resolve<Client>();

//_dependencies.Add(client.HeavyDependency);

Thread.Sleep(1000);

}

Console.WriteLine("Press any key to exit ...");

Console.ReadKey();

}

}

Experiment

Based on the dependency resolution strategy, the experiment is primarily divided into two cases: transient instantiation and singleton. Each of these two cases again have two more sub-cases based on the dependency’s external reference: no external reference and static external reference (on each instantiation, the injected dependency is also stored in a static list.) So four cases in total. In each case, we run the application from Visual Studio and observe the memory chart in Diagnostic Tools window for about 30 seconds.

Transient instantiation of the dependency

Unity’s default type resolution strategy is transient [1] (a new instance is created on each resolve.) Moreover none of the types in the project has ambiguos constructors or no abstract types are involved. As a result, no registration of types is needed at all; Unity resolves the types by convention.

Let’s analyze the result of the first case.

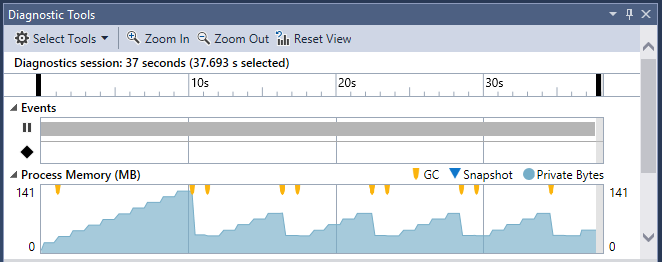

As the Visual Studio Diagnostic Tools’ memory chart shows, memory usage peaks to 141 MB however, it remains much lower on average. As the resolved Client instances has no references outside the iteration loop, they become eligible for collection as they go out of scope and the memory acquired by them are freed up by garbage collector periodically.

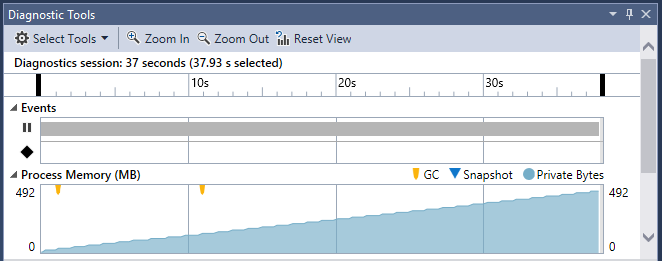

In the second case, the dependency instance is referenced outside the Client; we do it by uncommenting the second commented block in the applicatoin’s Main method; it appends the HeavyWeightDependency instance from each Client instance into a static list _dependencies; as a static field, the list is alive until the application is closed. Let’s see how does it affect memory usage.

This time things are worse (worst, in fact, among the four cases.) As the dependency is being referenced outside the client (in the static list _dependencies,) garbage collector can’t release the memory acquired by it even though the corresponding client instance goes out of scope. Progressing this way, the application will eventually run out of memory.

The dependency as a singleton

As we planned, now we repeat the above two cases but with HeavyWeightDependency registered as a singleton. In Unity, a type can be registered as a singleton by setting its lifecycle as ContainerControlledLifetimeManager. We uncomment the first commented block in the application’s Main method to have the registration done.

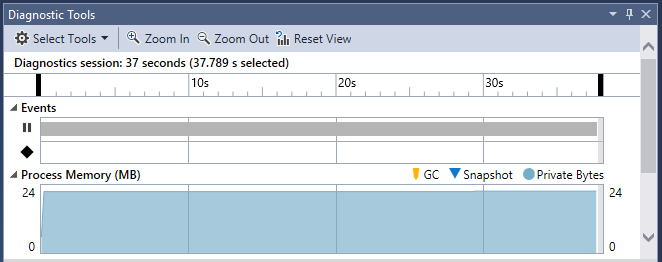

In the third case, we have the dependency as a singleton and it has no references outside the client.

This time memory jumps to 24 MB on startup and becomes stable; about half of it (~11 MB) is due to the HeavyWeightDependency instance and the rest is due to the application’s overhead. Creating multiple instance of Client doesn’t have any impact on memory.

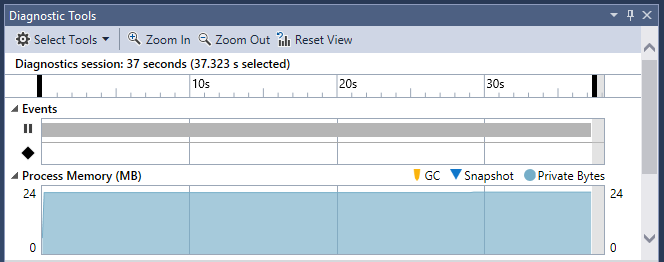

In the fourth—and the last—case, the dependency remains singleton but we reference it outside the client. Just as before, we do it by adding the dependency to the static list _dependencies.

This case is absolutely similar to the previous one! Having the dependency, a singleton, referenced anywhere in the application doesn’t have any impact on memory usage at all.

Conclusion

The current example illustrates the case of memory usage for objects with very high memory footprint. However, even a lightweight dependency with many references in a long running application can have significant effect. Identifying static dependencies and loading them as singletons help avoid unexpected memory footprints and a DI container can make the task easier. Once you start using a DI container, one of the earliest things you want to learn is how does it control object life cycle.

Further Reading

- Understanding Lifetime Managers. Unity documentation on its object lifetime management.

- “Dependency Injection with Unity” book (PDF and EPUB.) Comprehensive introduction to Microsoft Unity.